In my book, the Case of the Beth-el Stone, my heroes sail on the Duncan Dunbar from Australia to England, a ship captained by Henry Neatby. Like all of my novels, I weave real people and real events into my stories and Captain Henry Neatby was indeed a real person who captained the Duncan Dunbar in 1858, although the murder investigation in which he participated in my novel in 1864 is fictional.

Neatby must have been an interesting character, one of a breed of men at the time who stood apart from the average man. In my novel I describe him as one of the line’s most experienced men who had completed this journey several times before. I also describe the journey including the ship struggling through a storm; “What had once seemed a magnificent, towering, powerful ship when we boarded now seemed an insignificant, lonely, isolated speck at the whim of nature in the middle of an all-consuming world of huge, violent seas. The whole scene was awe-inspiring, animalistic, the ship relentlessly fending off attack after attack, like a deer at bay pulled down by the hounds, rising again and again valiantly out of the sea, shaking them off and surging forward with the spent sea cascading off the decks”.

What was this man really like, a man who faced down such dangers time and time again? I describe Neatby as “a reassuring, seasoned man with trimmed whiskers who usually wore a waistcoat, tie and leather jacket with his captain’s cap. He was often to be seen with a pipe, standing, watching, gauging the nuances of the sea and the weather. Always seemingly in command of his world”.

An author’s license here but there is evidence to back up my imaginings. He was a seasoned seafarer. On one voyage in 1836 he captained a convict ship, the Susan, and he later made voyages between England and Australia as Captain of other vessels - The Agincourt from Sydney to London in 1848; the Waterloo from London to Sydney via Port Phillip (Melbourne) in 1849.

In my earlier books, The Helots’ Tale, I describe two earlier convict ship voyages and based on that research, Neatby’s experience with the Susan was not atypical.

The voyage took 114 days, leaving Portsmouth on 16th October, 1835 with 300 male prisoners and a detachment of the 28th Regiment. Although most of the convicts came from England there were also 10 men from Scotland; 11 from Barbados; 2 from Demerara (now part of Guyana) and 3 from Tortola (British Virgin Islands). And 5 of the prisoners were ex-soldiers who had been court-martialled for desertion or striking their sergeant.

Convict ships tended to be poorly suited for the journey, tubs. The Government was not going to pay more than they needed to dispose of the ‘detritis’ of England. Even in a well-built ship it was not a journey that could be undertaken lightly with disease and shipwreck an ever-present threat. And, as with all convict ships, the Susan carried a Ship’s Surgeon, in this case a Scot by the name of Thomas Galloway, making his fourth and last voyage as a convict ship surgeon-superintendent at the extended age of 55. Six men died on the way.

Galloway described one of several old and very infirm men amongst the convicts, a James Curtis, who had “passed the greater part of his life as a small planter in Barbados and who is exceedingly indolent and obstinate”. He ended up having one of the other convicts act as a nurse for Curtis because he refused to do anything whatever for himself. But Curtis didn’t make it. He was one of those who died. In all, two died from scurvy, another three from diarrhoea and one from tabes (a progressive wasting of the body). (During an immigrant voyage five years later on which Galloway was the Surgeon, forty-one people died although an enquiry later found that there was no blame attached to him for the high mortality rate).

On more than one occasion I have come across examples of men and women eager to be transported despite the risks and Galloway noted in his journal that there were several men who had concealed that they had been in hospital when they were examined before boarding because they were so keen to be transported to New South Wales – a desire not that uncommon amongst the downtrodden poor of England at the time seeking a better life.

As Neatby navigated the last miles of the journey on 7th February, 1836 he had one further adventure. Entering Port Jackson (Sydney) harbour the Susan ran afoul of another ship, the Clyde while working up the harbour, losing her quarter gallery and boat, besides other damages.

Neatby’s travails were still not over. He was summoned to answer a charge of assault made by a seaman named William Jones who had been employed painting on the quarter deck, at the same time smoking a pipe. Neatby ordered him to quit his pipe or his work whereupon he exclaimed, 'Drop the tools and damn the work.' Neatby was not going to stand for that and had him placed in handcuffs until sunset. On this occasion, Neatby won the day, the judge dismissed the case and the reporter noted that “Captain Neatby appears to be cursed with a very disorderly crew; he has been frequently before the bench, but on every occasion has succeeded in defeating his accusers”.

Then, later in February, he charged his steward with stealing some corned beef and sugar. Apparently, when Neatby confronted him, he replied, “Damn me, Sir, it belongs to the King, you took it from the hold, and I gave it away”, but this time the judge ruled against Neatby.

My characterisation of Neatby in my novel is, I think, best supported by an article that I came across in The Sydney Morning Herald of 8th January, 1856. It is a ‘Testimonial to Captain Neatby’ presented by the passengers of La Hogue after a voyage from Plymouth to Sydney.

They describe him as an able and most careful commander and noted, “...the very liberal and efficient arrangements made for our comfort, convenience, and safety, during the whole period. We gratefully acknowledge the personal courtesy which has been invariably extended to each of us individually; whilst we must express our admiration of the indefatigable zeal and attention which have characterised your management of the remarkably fine ship which you now command”.

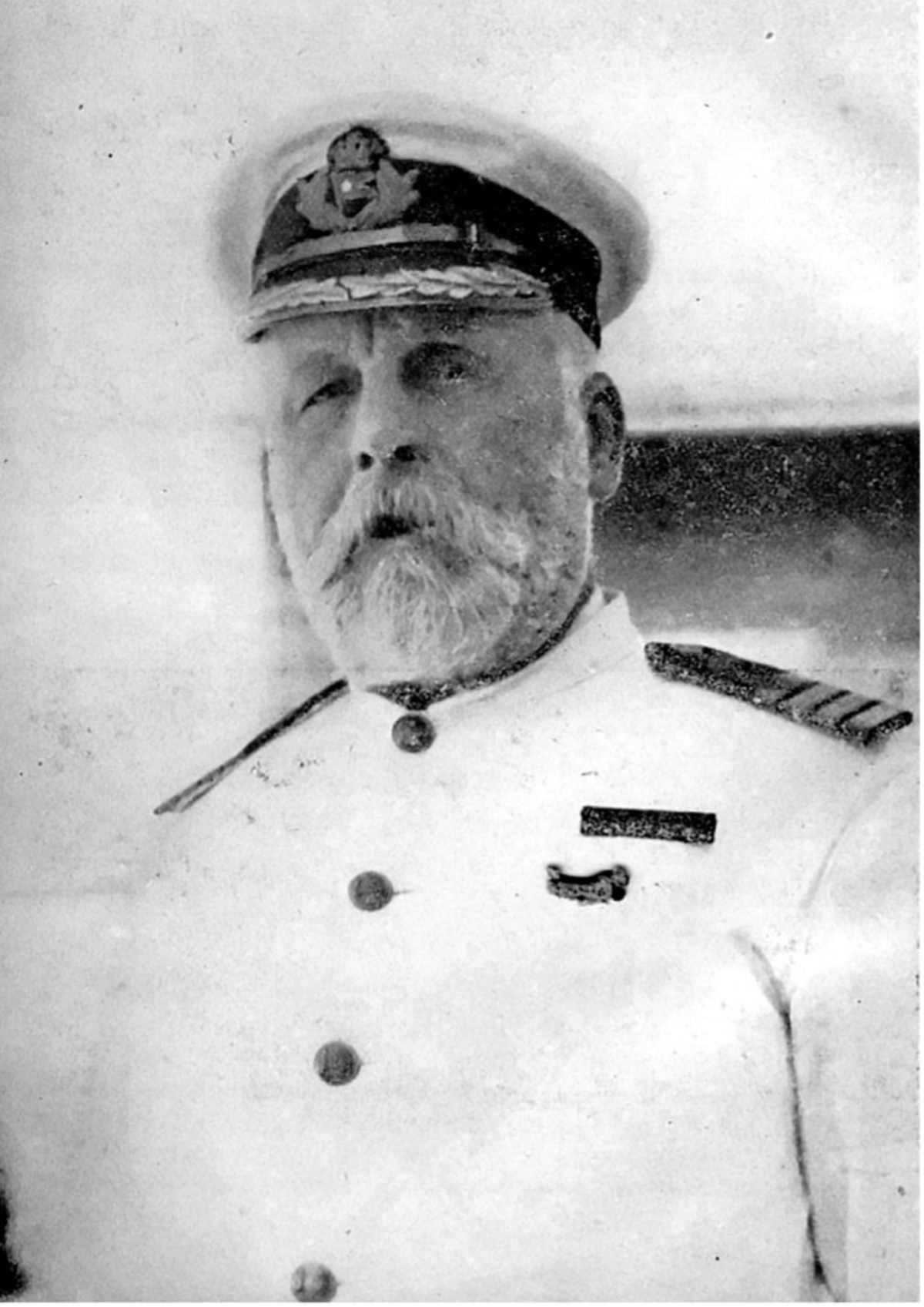

Having recently been to a Titanic exhibition, I can’t help but compare Neatby coping with elementary technology against the elements to Captain Edward Smith…..